Advanced Liquid Package Solution

A liquid filling machine is a machine that fills liquid products into packaging containers.

Liquid products are classified by their viscosity into the following types:

Fluid: Any liquid that can flow through a circular pipe at a certain speed under its own gravity. The flow rate is mainly affected by the fluid’s viscosity and pressure, with a general specified viscosity range of 1–100 centipoise, such as alcohol, fruit juice, milk, soy sauce, etc.

Semifluid: A liquid that can only flow through a circular pipe under pressure greater than its own gravity, with a viscosity range of 100–1000 centipoise, such as sponge cake oil, savory sauce, meat paste, etc.

Viscous fluid: Products with a viscosity exceeding 10,000 centipoise, which are not classified as fluids or semifluids. Examples include pastes and similar products.

For low-viscosity liquids, they are divided into non-carbonated and carbonated types based on whether they contain carbon dioxide gas; and into soft drinks (non-alcoholic) and hard drinks (alcoholic) based on whether they contain alcohol.

The flow characteristics of fluids are also affected by factors such as temperature, viscosity, solid particle content, decomposability, surface tension, or foaming properties.

Packaging containers are currently classified by material mainly into glass bottles, metal cans, paper containers, plastic bottles, etc., and also into:

Rigid containers: Any container made of metal, glass, ceramic, or plastic that can withstand a downward pressure of 15 pounds without deformation and does not leak liquid after being sealed with a cover.

Semi-rigid containers: Any container made of lightweight plastic (usually blow-molded or thermoformed) or cardboard and its composite paper materials that does not leak liquid after being sealed with a cover.

Non-rigid containers: Any container made of plastic film, metal foil, plastic composite film, or composites thereof (e.g., bags, which generally require the filling system to be equipped with a bag-making device). Piston volumetric filling is commonly used, where the filling system fills a fixed volume of liquid into containers produced by this device.

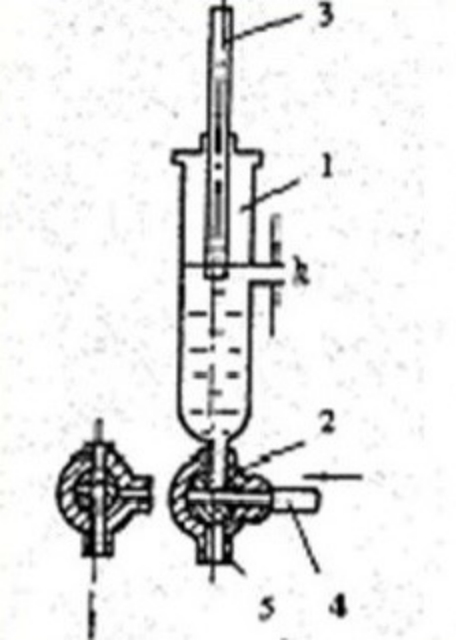

Rotary filling machine

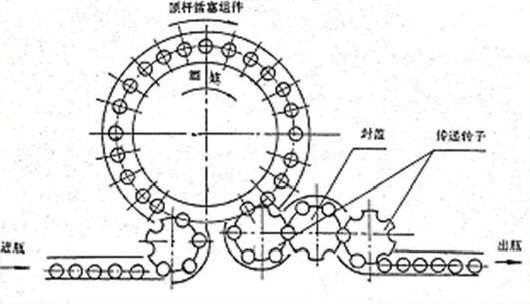

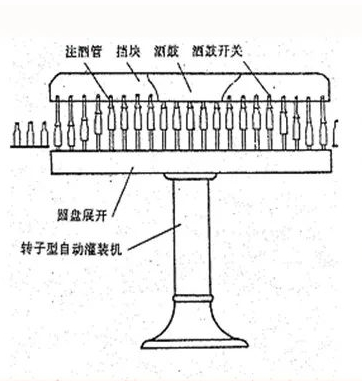

Bottles to be filled are fed into the bottle infeed mechanism of the filling machine by a conveying system (generally input via a conveyor belt after a bottle washer) or manually. The bottles are driven by the filling machine’s turntable to rotate around the main vertical axis for continuous filling. When rotated nearly one full circle, the bottles are filled, and then sent to the capping machine by the turntable for capping (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Top view of a bottle during the filling process

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of a bottle being expanded during filling

This type of filling machine is most widely used in the food and beverage industry (e.g., for filling soda, fruit juice, beer, milk). It mainly consists of a fluid delivery system (feeding system), container delivery system (bottle feeding system), filling valves, a large turntable, a transmission system, a machine body, and an automatic control system. Among these, the filling valve is the key to ensuring the normal operation of the filling machine.

Linear filling machine

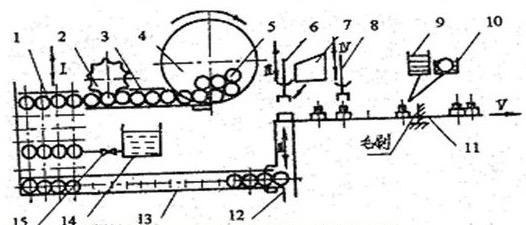

Filling bottles move along a straight line for row-by-row filling (see Figure 3). When a row of empty bottles is delivered, the bottle push plate pushes them forward once; when they reach below the filling nozzles, the valves open for filling, with intermittent operation.

Figure 3 Working principle diagram of a linear filling machine

I.Quantitative filling, II.Capping, III.Cap tightening, IV.Labeling,V.Cartoning and boxing

1.Bottle push plate, 2.Limit dial, 3,11,13.Conveyor belt, 4.Conveyor disk, 5.Bottle,

6.Capping mechanism, 7 .Hopper, 8.Tightening mechanism, 9.Label box, 10.Paste box, 12.Material push plate, 14.Liquid storage tank, 15.Filling pipe

Compared with rotary filling machines, this type has a simpler structure and is easier to manufacture, but it occupies a larger area and operates intermittently, which limits the improvement of production capacity. Therefore, it is generally only used for filling non-carbonated liquids and has great limitations.

Automatic filling machine

This type can be divided into: single-machine automatic machines and combined automatic machines (which can include continuous processes such as bottle washing, filling, capping, labeling, and cartoning). Automatic filling is most commonly controlled by mechanical transmission.

In addition,there are various classification methods based on filling methods, closing and quantitative devices,with specific details shown in Table 1:

Table 1 Classification of Filling Machines

No. | Classification Type | Type, Technical Characteristics, Filling Method | |||

1 | By automation level | Manual filling machine | Semi-automatic filling machine | Unit automatic filling machine | Liquid packaging combined automatic machine |

2 | By mechanical structure | Single-row type | Multi-row type | Rotary type | Rotary type |

3 | By filling method | Pressure filling at constant liquid level | Pressure filling at variable liquid level | Vacuum filling | Pressure filling |

4 | By closing device | Cock type | Valve type | Slide valve type | Pneumatic valve type |

5 | By quantitative device | Measuring cup dosing | Liquid level dosing | Metering pump dosing | Ampoule dosing |

The physical and chemical properties of various liquid products vary. To maintain the product characteristics unchanged during filling, different filling methods must be adopted. Common filling methods used by filling machines are as follows:

Also known as the pure gravity method, it involves liquid flowing into packaging containers by its own weight under atmospheric pressure. Most free-flowing non-carbonated liquids can be filled by this method, such as Baijiu (Chinese liquor), fruit wine, milk, soy sauce, vinegar, etc.

Also called the pressure-gravity filling method, it operates under pressure higher than atmospheric pressure. First, the packaging container is inflated to create air pressure equal to that in the liquid storage tank, then the liquid flows into the container by its own weight. This method is widely used for filling carbonated beverages like beer, soda water, sparkling wine, etc. It reduces carbon dioxide loss in such products and prevents excessive foaming during filling, which could affect product quality and filling accuracy.

Filling is carried out under pressure lower than atmospheric pressure, and it can be implemented in two ways:

Differential Pressure Vacuum Type

The liquid storage tank is at atmospheric pressure, while the packaging container is evacuated to create a vacuum. Liquid flows and fills the container due to the pressure difference between the storage tank and the container. This method is commonly used in China.

Gravity Vacuum Type

Both the liquid storage tank and the packaging container are evacuated to the same vacuum level, then the liquid flows into the container by its own weight. This method has a more complex structure and is rarely used in China.

The vacuum method has a wide range of applications: it is suitable for filling liquids with slightly higher viscosity (e.g., oils, syrups) and vitamin-containing liquids (e.g., vegetable juice, fruit juice). Creating a vacuum in the bottle reduces contact between the liquid and air, extending the product’s shelf life. It is also used for filling toxic materials (e.g., pesticides) to reduce the escape of toxic gases and improve working conditions.

Mechanical or air pressure is used to force the material into the packaging container. This method is mainly for filling high-viscosity pasty materials, such as tomato sauce, meat paste, toothpaste, cosmetic balm, etc. It can also be used for filling soft drinks like soda water—soda is directly filled into unpressurized bottles using its own gas pressure, increasing filling speed. The foam formed is easy to dissipate (as soda contains no colloids) and has little impact on filling quality.

Filling is completed using the siphon principle. It is the earliest filling method, easy to understand with a simple principle, but rarely used now.

The correct selection of the above filling methods depends on comprehensive factors including the liquid’s process performance (viscosity, density, carbonation, volatility), product process requirements, and the mechanical structure of the filling machine. For general non-carbonated edible liquids (e.g., bottled milk, bottled alcohol), either the atmospheric pressure or vacuum method can be used. Using a high-vacuum vacuum method is more beneficial for reducing oxygen content in the liquid and extending shelf life; it also features a simpler filling valve structure and less liquid leakage. However, a higher vacuum level may cause loss of alcohol aroma, and the vacuum method has higher equipment costs than the atmospheric pressure method. Note that a single method is not always required—combinations are possible. For example, to reduce oxygen content in beer and prevent turbidity during storage:

One approach is to evacuate the bottle first, then fill it under isobaric conditions with carbon dioxide (vacuum-isobaric method).

Another approach is to pressurize the bottle with carbon dioxide to equal pressure, channel the displaced air into a separate gas return tank (not the liquid storage tank). Filling is done under isobaric conditions in the early stage, and gas return speed is increased in the later stage to create a pressure difference with the storage tank, boosting filling speed (isobaric-pressure (differential pressure) method).

Accurate quantitative filling is directly related to product cost and affects consumer trust. Quantitative filling for packaged goods is generally divided into weight metering and volume metering:

Weight metering: Requires weighing scales, leading to a more complex machine structure. It is suitable for solid materials with variable density and usually needs an electrical circuit for electromechanical coordination.

Volume metering: Features a simpler structure with no need for electrical coordination, and is commonly used for liquid products.Three common volume metering methods for liquids are:

Quantitative filling is achieved by controlling the liquid level height in the container. The volume of liquid filled each time equals the inner volume of the bottle at a specific height, so it is commonly called "bottle-based metering". This method has a simple structure, no auxiliary equipment, and is easy to use, but is not suitable for products requiring high filling accuracy (as bottle volume precision directly affects filling volume accuracy).

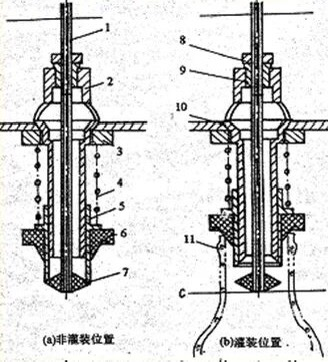

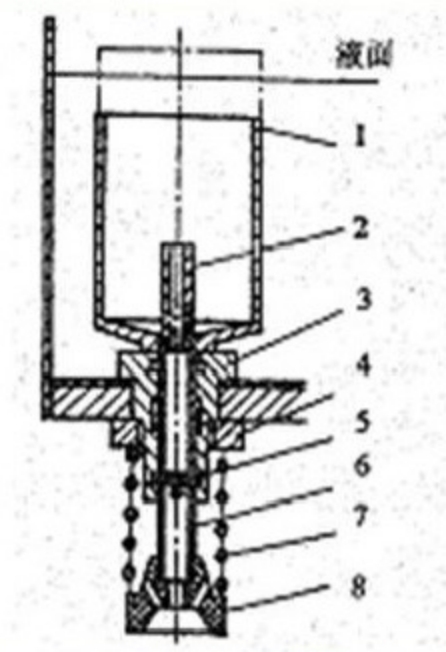

Figure 4 Principle diagram of liquid level control quantitative method (for filling sterilized fresh milk, fresh fruit juice, etc.):

• (a): Non-filling position; (b): Filling position.

When the rubber pad 6 and sliding sleeve 5 are lifted by the rising bottle 11, a gap forms between the filling head 7 and sliding sleeve 5, allowing liquid to flow into the bottle. Air in the bottle is exhausted to the liquid storage tank through the exhaust pipe 1. When the liquid reaches the cross-section c–c of the exhaust pipe nozzle, air can no longer escape. As liquid continues to fill, the liquid level rises above the nozzle, compressing the remaining air in the bottle mouth. Once pressure balance is achieved, liquid stops entering the bottle and rises along the exhaust pipe to the same level as the liquid storage tank (based on the communicating vessel principle). The bottle then descends, and the compression spring 4 reseals the filling head and sliding sleeve; liquid in the exhaust pipe drips into the bottle, completing quantitative filling. The liquid level height in the bottle remains constant under stable operating conditions.

To adjust the filling volume, simply change the position of the exhaust pipe nozzle inside the bottle.

Liquid is first filled into a measuring cup for quantification, then poured into the bottle—each filling volume equals the measuring cup’s volume.

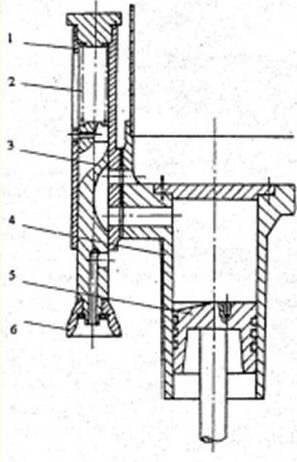

Figure 5 Schematic diagram of cock-type measuring cup metering mechanism:

1. The three-way cock 2 is in the position shown on the left; liquid flows into the measuring cup 1 through the liquid inlet pipe 4 under static pressure, and air in the cup is exhausted through the thin pipe 3.

2. When the liquid level in the cup reaches the lower edge of the thin pipe, air can no longer escape. However, the higher liquid level in the storage tank causes the liquid level in the cup to rise above the pipe’s lower edge, compressing the air inside until pressure balance is achieved.

3. The liquid level in the thin pipe 3 rises to the same level as the storage tank (communicating vessel principle).

4. The three-way cock is rotated 90° counterclockwise (left position), isolating the liquid in the measuring cup from the storage tank, and the liquid (including that in the thin pipe) flows into the bottle.

To adjust the filling volume, adjust the height of the pipe in the measuring cup or replace the measuring cup.

(Continuation of Section 2 Basic Principles of Filling)

Figure 6 Structure of a Direct-Acting Measuring Cup

When there is no bottle to be filled below, the measuring cup 1 descends under the action of the spring 7 and is immersed in the liquid in the storage tank, allowing the liquid in the tank to flow into and fill the measuring cup along its periphery. Then the bottle to be filled is lifted by the bottle support; the bottle mouth lifts the bell mouth 8, liquid inlet pipe 9, and measuring cup 1 together, lifting the measuring cup above the liquid surface. The upper and lower holes on the partition in the liquid inlet pipe are connected to the middle of the valve body 3. As a result, the liquid in the measuring cup flows down through the adjusting pipe 2, into the middle groove of the valve body 3 via the upper hole of the partition, and then into the bottle to be filled through the lower hole of the partition and the lower end of the liquid inlet pipe. Air in the bottle escapes through the air vent on the bell mouth. Quantitative filling is completed when the liquid level in the measuring cup drops to the upper end face of the adjusting pipe 2.

The volume of the measuring cup can be adjusted by changing the height of the adjusting pipe 2 in the measuring cup or replacing the measuring cup. This structure is suitable for filling alcoholic products.

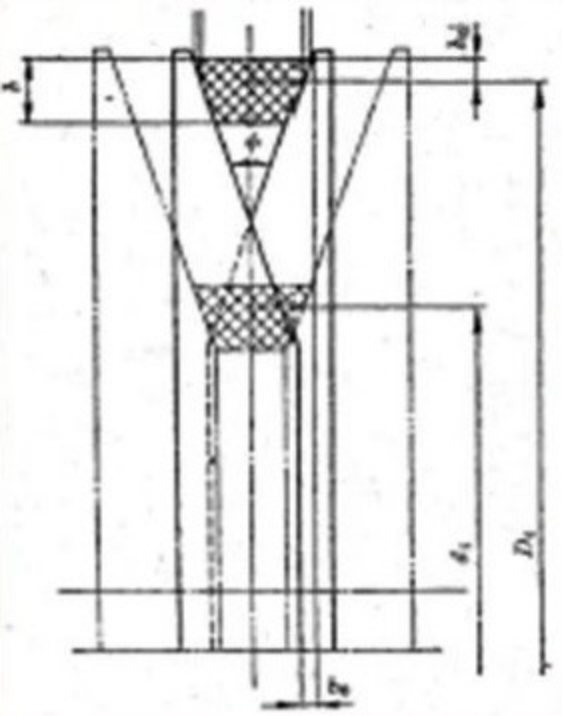

This is a quantitative filling method using the pressure filling principle. It generally uses power to control the reciprocating motion of a piston: the material is sucked from the storage cylinder into the piston cylinder, then pressed into the packaging container. The volume of material filled each time is controlled by the stroke of the piston’s reciprocating motion. Figure 7 shows the principle diagram of quantitative filling of tomato sauce using a metering pump.

Figure 7 Principle diagram of the measuring cup quantitative method

1.Valve body, 2.Spring, 3.Slide valve, 4.Piston cylinder, 5.Piston, 6.Bell mouth

The piston 5 is driven by a cam (not shown in the figure) to reciprocate up and down. When the piston moves downward, the sauce flows into the piston cylinder 4 through the crescent groove of the slide valve 3 at the bottom hole of the storage tank under the action of gravity and pressure difference. When the container to be filled is lifted by the bottle support and pushes against the bell mouth 6 and slide valve 3, the spring 2 is compressed and the crescent groove on the slide valve rises, isolating the storage cylinder from the piston cylinder. The discharge hole on the slide valve connects to the piston cylinder, and at the same time, the piston moves upward under the cam’s action, pressing the sauce from the piston cylinder into the container to be filled. When the filled container descends with the bottle support, the spring 2 forces the slide valve to move downward, and the crescent groove on the slide valve reconnects the storage cylinder to the piston cylinder for the next filling cycle.

If there is no container to be filled on a bottle support, even if the piston reaches a certain working position and is supposed to move upward under the cam’s action, the crescent groove on the slide valve does not rise. Thus, the sauce is pressed back into the storage cylinder without affecting the normal progress of the next filling cycle.

To adjust the filling volume for this method, simply adjust the piston stroke.

• Quantitative accuracy: The first method (liquid level control) is less accurate than the latter two, as it is directly affected by the bottle volume precision and the sealing degree of the bottle mouth.

• Mechanical structure: The first method is the simplest, so it is widely used.

The correct selection mainly depends on the required quantitative accuracy of the product. For example:

• China’s ministerial standard for 640-milliliter beer is ±10 milliliters, while foreign standards are ±3 milliliters.

• For bottled alcohol and other products filled by liquid level height, the error should not exceed 1.5 millimeters, and the volume error should be controlled within ±0.4%. The more valuable the product, the smaller the allowable error.

Selection also considers the process characteristics of the liquid: for filling carbonated beverages, using the measuring cup method may reduce accuracy due to foam in the storage tank, so the liquid level control method is generally preferred in such cases.

After the bottle washer cleans the inside and outside of the bottles, qualified bottles (after quality inspection) are conveyed by the conveyor belt to the limiting mechanism of the automatic filling machine, arranged at a specified distance, and sent to the bottle dial wheel. The bottle dial wheel accurately feeds the bottles into the bottle lifting mechanism. The lifting mechanism jacks up the lifting piston, and the bottle rises accordingly. The bottle mouth then opens the air valve of the filling valve for inflation and pressure equalization, followed by opening the liquid valve for filling. After filling, pressure is released, and then the liquid valve and air valve are closed.

After filling is completed, the bottle lifting mechanism immediately enters the descending slideway. Under the action of the descending slideway, the lifting piston cylinder is forced to descend by the slideway, so the filled bottle drops to the lowest position. After rotating a certain angle, the bottle enters the bottle pushing mechanism, is pushed out by it, and sent for capping—completing one working cycle of the entire filling process.

Rotary automatic filling machines are powered by electric motors, with a power range of generally 1–3 kilowatts. The motor speed is usually very high, while the filling machine speed is only a few revolutions per minute, which cannot meet filling requirements. Therefore, a reasonable speed change system is required for its transmission.

Some filling machines use speed-regulating motors for direct stepless speed change, but this transmission method has high requirements for the motor (e.g., dustproof, waterproof) and is relatively expensive.

Requirements for the transmission part of rotary filling machines:

1. Stable transmission

The main machine completes filling on a liquid cylinder, and accurate bottle infeed, outfeed, and filling all require stable working conditions.

2. Simple structure of the transmission system

A simple transmission system reduces power consumption, makes it easier to achieve equipment precision, and facilitates maintenance.

3. Safety devices

A common problem with rotary filling machines is bottle jamming. Safety devices should be designed to automatically stop the machine or trigger an alarm in case of faults, for timely troubleshooting.

To adapt to manufacturers’ frequent product changes, give full play to equipment potential, achieve multi-purpose use of one machine, and improve equipment adaptability, the speed of the filling machine must be adjustable (speed regulation) to meet requirements.

In addition, the design of the transmission system should consider the convenience of installation, commissioning, and maintenance, meet ergonomic requirements for worker convenience, minimize maintenance time, and be easy to repair and maintain.

The machine needs to be adjusted according to usage and product conditions; several common adjustment methods are introduced below:

1. Adjustment of liquid cylinder level

The liquid level in the cylinder directly affects filling speed. If the level is too low, bottles may not be filled during the specified filling angle. Therefore, the liquid level in the cylinder of the filling machine must be adjustable and controlled at an appropriate position, and remain basically stable during filling to ensure a steady filling speed.

2. Adjustment of filling volume

Most filling machines use bottle-based quantification. When replacing bottles of different capacities, the filling volume is adjusted by changing the height of the piston core in the lifting mechanism (thus changing the bottle capacity). For filling machines with measuring cup quantification, the filling volume is adjusted by changing the volume of the measuring cup.

3. Adjustment of rotational speed

The common speed-regulating device for filling machines is mechanical stepless speed regulation; here we only explain the principle of V-belt mechanical stepless speed regulation:

As shown in Figure 4.29 (Principle diagram of belt stepless speed regulation), two pairs of cone pulleys are connected by a special wide V-belt (stepless speed regulation belt). Shaft I is the driving shaft, and Shaft II is the driven shaft. When a fixed speed V is input to Shaft I, turning the handle 1 tightens the cone pulley via gears and threads, increasing the effective radius of the driving pulley. Since the circumference of the stepless speed regulation belt is constant, the two cone pulleys on Shaft II compress the spring, reducing their effective radius—and the output speed of the shaft increases.

Figure 8 Principle diagram of the measuring cup quantitative method

As shown in Figure 8 (Principle diagram of belt stepless speed regulation), two pairs of cone pulleys are connected by a special wide V-belt (stepless speed regulation belt). Shaft I is the driving shaft, and Shaft II is the driven shaft. When a fixed speed V is input to Shaft I, turning the handle 1 tightens the cone pulley via gears and threads, increasing the effective radius of the driving pulley. Since the circumference of the stepless speed regulation belt is constant, the two cone pulleys on Shaft II compress the spring, reducing their effective radius—and the output speed of the shaft increases.

Conversely, when the cone pulleys on Shaft II are retracted, they tighten under spring action, reducing the output speed. This stepless speed regulator operates stably with a simple structure, but has a narrow speed regulation range; its slip rate changes with load, and the output speed changes approximately symmetrically with the input speed.

It can only be used for speed matching adjustment inside the transmission chain, not in transmission systems requiring accurate transmission ratios. It is only suitable for low-torque transmission; for high torque, its size becomes too large, and its speed change range is usually 2–4.

The three adjustment methods introduced above are relatively simple and interrelated. Therefore, attention should be paid to the mutual relationship of each part when adjusting the machine.

Although such filling machines have advantages like compact structure and high continuous production efficiency, they also have the following problems:

1. Complex structure (e.g., the filling system is intricate). The development direction of light industry machinery is to pursue simple structure, small size, and light weight.

2. Bulky transmission mechanism (e.g., the main shaft uses large bearings).

3. High cost (e.g., liquid cylinders made of stainless steel or cast copper increase costs).

4. High processing requirements, especially for sealing.

In addition, the transmission system is located under the main machine, making maintenance inconvenient. Meanwhile, the rotational speed of the main machine is limited by centrifugal force, which also restricts the improvement of production capacity.

By continuing to use the site you agree to our privacy policy Terms and Conditions.